‘Conditions In The Niger Delta Compel More Interventions Through Good Causes’

‘Conditions In The Niger Delta Compel More Interventions Through Good Causes’

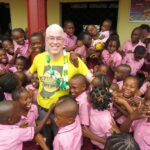

Professor Scott Pegg, who teaches political science at the School of Liberal Arts, Indiana University, United States of America (U.S.A) in this interview with Thenewexperiencenewspaper in Lagos, says parlous conditions in the Niger Delta region makes it imperative to embark on good causes there. His intervention programmes, especially in Ogoniland include building the Bebor Group of Schools in Bodo, water and sanitation projects, providing basic immunisations, deworming treatment for children and most recently, a pilot nutrition programme. These have earned him the traditional title of Mene Eedee I of Bodo in Gokana Local Council of Rivers State. He says of all the things people say about Nigeria, the country and its people remain one of the most pleasant around the world. Excerpts:

What spurred your interest in building the Bebor Schools in Bodo Community of Ogoni in Rivers State?

I initially became interested in the Niger Delta and in the impact of oil production in the run-up to the hangings of Ken Saro-Wiwa and eight other Ogoni leaders by the the late General Sani Abacha dictatorship in 1995. I heard Saro-Wiwa’s younger brother, Dr. Owens Wiwa speak about 10 months after the hangings, while I was doing my Ph.D at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada. After his visit, I joined other activists in the Vancouver area to form the Ogoni Solidarity Network. We started doing protests at Shell gas stations in Vancouver. Ultimately, we protested at all 17 Shell stations in Vancouver and we conducted 52 consecutive weeks of protests from the first anniversary of the hangings to the second anniversary. Wanting to be better informed and more knowledgeable, while doing the protests was what initially spurred me to do more academic research on the Niger Delta, oil production in sub-Saharan Africa and what is now commonly referred to as the “resource curse.”

My first visit to Nigeria was in April 2000 to attend a memorial service for Ken Saro-Wiwa in his home village of Bane, Rivers State. While there, Dr. Owens Wiwa asked a Bodo indigene named Patrick Naagbanton to show me around. Patrick took me to Bodo to meet his mother and his family and introduced me to Reverend Moses Nyimale Lezor, the director of Bebor Model Nursery/Primary School. Reverend Moses subsequently sent me a letter telling me where the school was at that time and what it hoped to do moving forward. At the time, my wife of almost 18 years, Tijen Demirel-Pegg and I were about to get married. We decided that instead of people getting us wedding gifts, we would ask them instead to donate funds to help Bebor Model Nursery/Primary School.

The total extent of my initial vision was that I knew 20 people who would donate $100 and that would be $2,000 and they could do something with that. I had absolutely no idea that I would still be doing this 19 years later and no idea that we would expand from helping one school in one village to four schools in three villages or that we would move from classroom building construction to water and sanitation to providing basic immunizations and deworming treatment and, most recently, into a pilot nutrition program.

One could argue that considering the volatile nature of that part of the Niger Delta region of Nigeria over the years, it took great courage to establish the schools there?

The Niger Delta is certainly not the most stable, peaceful or easy environment to operate in. That’s part of what makes it important to work there. The great American businessman and philanthropist Warren Buffett once said that the biggest difference between business and philanthropy was that in business you looked for the quickest and easiest way to make money and the quicker or easier the better. In philanthropy, he said, if you are not working on something difficult, something that has defeated other groups or organizations or proven hard to solve, then you are not doing good philanthropy. The rural Niger Delta is a hard and challenging environment to work in and that is one of the reasons we need to be there.

I never travel with armed security guards and the main thing I do is rely on the advice of my local contacts. There are times that they tell me we cannot go to a certain village or that we can’t do something, and I never argue with them about that. In all the years we have been doing this, there was only one time, in 2008, when kidnapping was reaching epidemic levels in Port Harcourt and the surrounding areas that my friends asked me not to visit Nigeria. After hearing from them, I cancelled my trip and changed my plans. Other than that, I have been able to visit Nigeria and the villages we serve in Rivers State whenever I have wanted or been able to. Not counting members of my immediate family, we have brought nine different westerners with us to see the schools and visit the villages we work in. None of them have ever had a problem and all of them enjoyed their time in Nigeria. On my trip a few months ago, I took my 12-year-old son Kerem with me for the first time. He loved Nigeria! Obviously, I wouldn’t do that if I thought it was too dangerous for him.

It could also be argued that you took a risk by establishing the schools in Bodo, giving Nigeria’s socio-economic, political, infrastructure and energy crisis?

We have taken a lot of different risks with this project. Working in Nigeria is one of them. Before we started working with Timmy Global Health in 2002, our donors had to write a check payable to me and take it on my word that the money would actually go to help Bebor. Timmy Global Health primarily works on health-related issues in Latin America. They took a risk in 2002 by taking on a more education-focused project in a completely different part of the world. Every time we have expanded to support another school – in Bane in 2003, in Bori in 2012, with St. Patrick’s Nursery and Primary School in Bodo in 2015, we have taken risks. We took a risk setting up our health program and we took another one more recently establishing a pilot nutrition program. Our donors still take risks by supporting a tiny, micro-scale initiative operating in rural Niger Delta villages when they could support local organizations or much bigger or better-established corporate charities. Coming back to Warren Buffett, I don’t think you can do good or important or innovative philanthropy without taking risks. It’s just not possible.

The biggest thing that balances out risk is trust. Everything I have ever done in Nigeria typically comes down to one person I know, trust and love recommending another person that they know, trust and love to me. We expanded to Bane and Bori because our school directress there is a member of the Wiwa family. We expanded to St. Patrick’s because one of my closest friends is a member of that church and said to me you need to meet the pastor there because he’s thoughtful, intelligent and committed to serving the rural poor. I wish I could tell you that I was the brilliant guy who thought that a major emphasis of our health program should be on deworming children. That idea came from Dr. Nabie Nubari Francis, our health program coordinator. I just said sure, sounds good, because I trusted him. Only months later did I learn that deworming is one of the cheapest, easiest and most cost-effective things you can do to improve children’s health and simultaneously increase their attendance at school and improve their education.

Similarly, I came across the bright guy who came up the idea of mixing crayfish, soybeans and millet as the main components of our nutrition programme. All three ingredients are locally available, and the parents and kids are familiar with them. That idea came from a local nutritionist, Pastor Ben Inaku whom Dr. Nabie knew. So, I guess for me, the rural Niger Delta is both a high risk and a high trust environment. Without the high trust part of that equation, we couldn’t work there.

Are you considering opening more schools in other parts of Nigeria, say in the Northeast where Boko Haram insurgency is ravaging that part of the country?

As you know, all sorts of educational problems, as well as health and nutrition problems are often far worse in northern Nigeria than in southern Nigeria. Your question is a good one because rural northern areas are where the most difficult or acute problems are found. That is particularly true of girls’ education, which is certainly something that we have tried to prioritise in our work in the Niger Delta.

We are not planning to expand to the north or too much beyond the parts of Rivers State that we currently operate in for two main reasons. First, our resources are extremely limited. I do this in my spare time. My regular job is teaching in the Department of Political Science at the Indiana University Purdue University, Indianapolis. Timmy Global Health is a small organisation with a dozen or so staff members. I would rather do a small number of things well than a larger number of things badly. Particularly, living in the United States, everyone is focused on growth here. We have grown, slowly or incrementally, but we’re not obsessed with increasing the number of villages we serve or the number of schools we serve. If we only serve four schools in three different villages for the next ten years, I’m fine with that. I would love to expand as or when resources permit but we are not interested in expansion just for the sake of expansion.

The second reason comes back to trust. It is not hard to find need. Indeed, I can find need in Indianapolis a few minutes from where I live. I see it every day on my commute to work. What is hard is finding people you trust, people you can develop long-term partnerships with. That’s probably the biggest asset I have in Rivers State. I’m sure there are a lot of those people in the north of the country, but I don’t personally know them.

How are the schools doing presently in Bodo and what are your future plans and projections?

We currently serve more than 1,200 children across the four schools we support. All of them have decent basic facilities in place – proper classroom buildings with roofs that don’t leak, boreholes for safer or improved drinking water, a small number of toilets, basic equipped sickbays. Technology is minimal to non-existent and could certainly be improved. I’d love to have solar panels to provide lights for the classrooms instead of just relying on natural light. Malnutrition is widespread and, funds permitting, I would love to expand our pilot nutrition program beyond the 50 kids we started with in Bodo to hundreds of kids. Some of our classrooms are quite crowded. In short, all our schools are doing fine and much better than they were before we started helping them but all of them could also be improved in several different ways.

Are there rewards mechanism for high performing staff and students of the schools?

Staff retention is a huge problem for us. A lot of teachers leave for what they perceive to be better opportunities or higher salaries in Port Harcourt. Some of the teachers we have trained to work in our sickbays have left to set up their own pharmacies. Other teachers that earn higher qualifications leave the rural areas entirely once they can do so. Keeping good teachers is a constant challenge for us.

There are some awards for high-performing students. One of the things I would love to do, funds permitting, in the future is provide scholarships for some of the students who graduate from the nursery and primary schools we support to attend secondary schools. At present, that remains an aspiration and not a reality.

What about standards? Are your academic programmes affiliated to the American pedagogical system?

No. The schools are Nigerian schools run by Nigerian school directors with classes taught by Nigerian teachers. I have not tried to change or interfere with the curriculum in any way. To date, a lot of our work has been focused on providing the physical infrastructure to enable good teaching and good learning to happen. It has also focused on keeping the kids healthy and free from preventable diseases, so they can attend school and learn while there. We have not tried to introduce any American or British or other pedagogies into the classrooms.

Apart from the education sector, are there plans to invest in other areas of interest for instance, tourism, agriculture, oil and gas in Nigeria?

No. Again, I am one individual with extremely limited resources. That’s something that must come from the business sector. I hope it does because Nigeria should be one of the best and most promising emerging markets of the 21st century. Our humble focus will remain on education.

How about your partners and funding of projects? Are you impressed about the management of the schools in Bodo?

Yes, profoundly. It is amazing to see how much Nigerians can accomplish with just a little bit of help. You can do so much more with a few thousand dollars in Nigeria than you could ever do in the United States. Working with some of our closest partners, the school directors and some of our friends and colleagues at the Center for the Environment, Human Rights and Development, who make our work possible is one of the most enjoyable and humbling experiences of my life. The dedication, creativity, talent and honesty of our local partners, while working on the ground in the villages, provide the foundation for everything we do. It simply would not be possible for me to do this work without them

How do you ensure accountability in projects execution, especially since you are based in the United States and visits Nigerian occasionally?

Excellent question! One main way that we have always done this is with photographs. If we send funding to put a rustproof roof on a building, then I want to see photos of that building with a finished aluminum zinc roof on it before we send another round of funding. That keeps the schools accountable and it also helps me raise funds since I can now tell our donors that we told you we were sending funds to put an aluminum zinc roof on this building and here you can see that we kept our promise and did what we said we were going to do. Now, when I ask you again for something else, you should have more confidence that it will happen because we did what we said we would do the last time. I also use my visits to the schools to do some of this. A few months before my trip last year we sent funds to our school in Bodo to install a new pumping machine to replace the one that was stolen a few months earlier. When I got to the school, I turned on the public water tap to make sure that it was running. Similarly, I flush toilets just to make sure they are still working. Last year, I joined the students in Bodo to eat with them during one of our nutrition programme feedings. One of the photos I took was of five or six of the students holding up their empty bowls to demonstrate that they were hungry, and they ate the food we provided them.

More generally, I always tell people that there is both a good reason and a bad reason that our schools are run by local Nigerians. The good reason is that I philosophically or intellectually understand the importance of local control. I know that if local people do not have a sense of ownership in our schools, they will never work. The bad reason is that I live in the United States and only visit Nigeria occasionally. I could not micro-manage this project even if I wanted to.

During your last visit to Nigeria, what impressed you most about the country, particularly in Rivers and Lagos states?

Lagos has fundamentally transformed since I first started coming to Nigeria. I remember the old domestic airport where you had to fight through a rugby scrum of people to buy your plane tickets with cash shortly before the flight. Now, you can book tickets online and check in after queuing in an orderly line. Beyond the airport, Lagos is just so visibly improved to the naked eye. You don’t have to have a PhD to understand that Lagos has changed significantly for the better in the last 10 years. You can just look around and see it.

The single biggest improvement in Rivers State that I noticed on this trip was the roads. There used to be horrible go-slows in Eleme between Port Harcourt and the villages that you could be stuck in for hours. There are now more options and a couple of major chokepoints have been fixed. Even down to the village level, the roads were noticeably improved since 2015 and dramatically better than they were a decade ago. Another thing that I was glad to see was fewer police checkpoints and seemingly better-behaved police than some of the ones I had previously encountered.

Across the country, the widespread use of cellphones is probably the single biggest improvement. When I first started coming to Nigeria, only the very elite had cellphones. Now, almost everyone does. I had a Nigerian SIM card inserted into my phone about 15 minutes after landing at MMA.

If you were to advise Nigerians and the government on education and other critical issues, what would that be?

The development literature is very clear on the signature importance of girls’ education. According to former UN Secretary General, Kofi Annan, “Study after study has taught us that there is no tool for development more effective than the education of girls.” Similarly, Harvard Economics Professor, Larry Summers, argues that there is probably no higher return on investment in the developing world than primary and secondary education for girls. Educated women tend to get married later, have fewer children, take better care of the children when they are in their wombs and in the critical first few years of their lives. They are more likely to start their own businesses and to be better managers of their family finances. Improving educational opportunities for girls and improving the status of women more generally will pay enormous dividends down the road for Nigeria.

Much less important than that, if you want to increase the number of visitors coming to Nigeria, you must make it easier for them to get Nigerian visas. Nigerian visa fees are comparatively very expensive and the number of hurdles you must cross to get one are among the highest and most difficult in the world. The energy and creativity found in Nigeria, what Emmanuel Macron spoke so well about during his recent visit to the New Afrika Shrine on the day I returned to the U.S., is inspirational. If you make it easier to come, more people will experience that, and, over time, it will lead to jobs and investments.

The New Experience Newspapers Online News Indepth, Analysis and More

The New Experience Newspapers Online News Indepth, Analysis and More